My Mother Gave Me Books (Statement of Purpose II)

The essay below is a continuation/companion of this essay about my father's sermons. It was delayed a week when Iran's rocket attack and the US vice presidential debate prompted a new post about extremism in the new Jewish year of 5785.

My parents are book people. They dated briefly when my father was just out of rabbinical school, getting set up again and again by the older members of his congregation. At the time, my mother worked at a bookstore. They went out, it fizzled, and that might have been it. Instead, nearly a year later, my father wandered into her shop looking for a book he’d read about. He didn’t know the author or the title, but she figured it out based on his vague description of the review. My father called her later that day and asked for another date.

I like imagining my parents in that bookstore because I see so much of myself in the story: my parent’s shared love of books; my mom’s early-20s retail job and preternatural recall of authors and titles.

My mom reads two newspapers a day, or at least peruses them cover to cover: the Times and the Post, still delivered ink-on-paper daily to my parents’ home. She loves audiobooks, listens to them on drives to visit my grandmother or cooking in the kitchen which is the nerve center of my childhood home. She is the only person I know who has been part of the same book group for more than thirty years where people show up having actually read the book. She moves through novels at a rapid clip, piles them on the low shelves beneath the TV in my parents’ bedroom until they accumulate and she moves them to the basement, which is lined on three walls with bookshelves from floor to ceiling. More than any of my English teachers growing up, she taught me to read fiction.

There was a period in middle and high school when I used to plow through my dad’s old Ballantine paperbacks of Tolkien, Frank Herbert, Arthur C. Clarke, and Isaac Asimov, but I owe the better part of my reading tastes to my mom. We read widely, but tend toward the literary. We each avoid and gravitate toward certain genres (we both steer away from romance, while I am quicker to reach for story collections and speculative work, and she is fonder of historical fiction). But overall they are broad and dictated by the characteristics important to a former bookseller and English major–characterization, pacing, the quality of the sentences, the ability to follow through on an ambitious idea, the emotional experience facilitated by the text.

When I was a child, she kept my bedroom shelves stocked with authors recommended by librarians and booksellers, lauded by reviewers, passed down from my older sister, endorsed by the children of her friends. I think about the origins of my reading life and return to three novels I read between fifth and seventh grade, each a Newbery winner given to me by my mother, and still among my favorite books: Lois Lowry’s The Giver, in which Jonas learns his society is corrupted by the things it believes protects it; E.L. Konigsburg’s The View From Saturday, in which the Souls stick up for Mrs. Olinski and make each other less alone; and Ellen Raskin’s The Westing Game, in which the residents of Sunset Towers heal each other even as they believe they must tear each other down to get ahead.

Somewhere in the past I am stretched out on the multicolored comforter in my childhood bedroom, eleven, twelve, thirteen years old, reading these novels and learning their pedagogy of connection and frailty, loneliness and love; the need to resist, to define ourselves by what we resist, to reach for something.

It is not lost on me that two of these novels were written by Jewish women. The Jewish characters are not all that is Jewish about Raskin’s The Westing Game or Konigsburg’s The View from Saturday. There is something in the point of view, the sense of humor, the thematic questions, that make these novels Jewish.

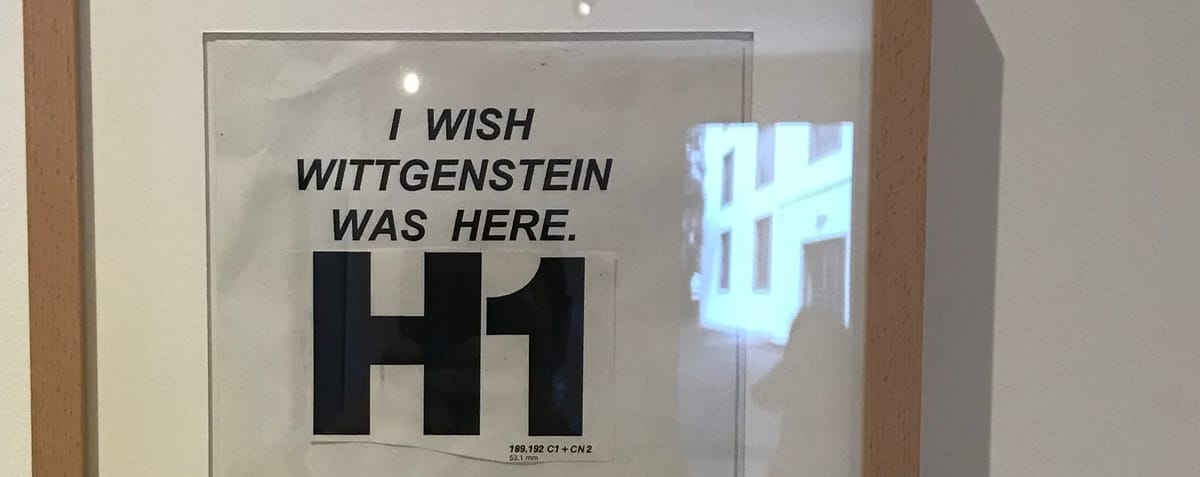

My dad reads fiction too, but not as often. I have heard him say his favorite novelist is Charles Dickens and I know him to have a fondness for John Steinbeck. These days, he favors detective stories, particularly those with a strong sense of place and a colorful protagonist. His relationship with fiction reminds me of something I once read about Ludwig Wittgenstein–the 20th century secular Jewish philosopher with whom my father and I share a fascination–who used to unwind by watching Westerns from the front row of his local cinema.

In his early work, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus–a thin treatise of staggering clarity that reads like a mystical text–Wittgenstein argues that there are certain philosophical problems we will never solve, existential questions we will never answer. The purpose of philosophy, as he understood it in this early work, is to “erect a wall where language ends anyway.” In that sense, the answers to the biggest questions posed by existence are not accessible to us, because they lie outside our ability to conceive of and communicate about the state of the world.

The closer we get to the unknowable, the side of the wall where language cannot go, the weirder and harder to elucidate these big questions become. Language literally breaks down:

Why is there matter? Where does “the past” go? How does meaning happen? How is it that two people somehow amounts to more than one human animal and another?

Religion is one way of making sense of the landscape near the wall–the questions can be posed in distinctly Jewish terms: What does it mean that all people are created in God’s image? What does it mean to be a partner in an ongoing creation? What does it mean that every Jew was present at Mount Sinai? Why does God keep a Book of Life? What is the nature of a covenant?

Books are another. The books my mom and I love the most leave us laughing and lumpen throated, bear a stubborn, broken grace that lingers for days after we read them; they bring us within the shadow cast by Wittgenstein’s wall, to be eased by its shade and awed by the indescribable profundity on the other side.

This is what religion and narrative and literature and art share: the ability to deliver an experience of clarity by other means, a glimpse beyond the wall. Books and Judaism are where I go to search out these experiences, to an extent where they can feel to me like one continuous field of play.

Before I went to fact check this newsletter, I assumed Lois Lowry was Jewish, too, because she wrote Number the Stars. She is not, but like The View from Saturday and The Westing Game, The Giver is nevertheless, for me, a Jewish novel. It features no Jewish characters–the novel’s anti-Utopian society is free of all religion, if I recall correctly–and was not written by a Jewish author, but the novel is still Jewish. How else am I meant to describe a book that draws such close associations between memory, culture, and redemption? That might be because of how I read it, or it might be because it’s just undeniably there in the novel, but it is reflexively true to me. That is the why of this newsletter, to write in service of that reflexivity.

Which we will really start to do next week, with the first installment of the Jewish non-Jewish Book Club, reading Emily St. John Mandel's Station Eleven. Until then,

Take care,

az

p.s. If you’re reading this in an email and you’ve made it this far, I encourage you to forward it on to anyone in your life who might find it interesting. And if you aren’t subscribed, I invite you to do so here, at any level. You may even find that you have something to contribute to the project; I would love to host reader essays if that ever makes sense in this space. In the meantime, if you have something you’d like to add to the conversation, feel free to reply here or zip me an email at jewishenglishmajor@gmail.com and share your thoughts. I’ll round up a selection of replies and share them here as we go.

p.p.s. This newsletter is relatively new. Start at the beginning. Or head over to the about page.

p.p.p.s If you enjoyed this essay and would like to try writing creative non-fiction with a Jewish spin, consider taking my class through Tamid of Hebrew College, Jewish Creative Writing Workshop: Memoir & Personal Essay, beginning October 21.